Sonic Interpolation: A Conversation with Artist Chukwudubem Ukaigwe

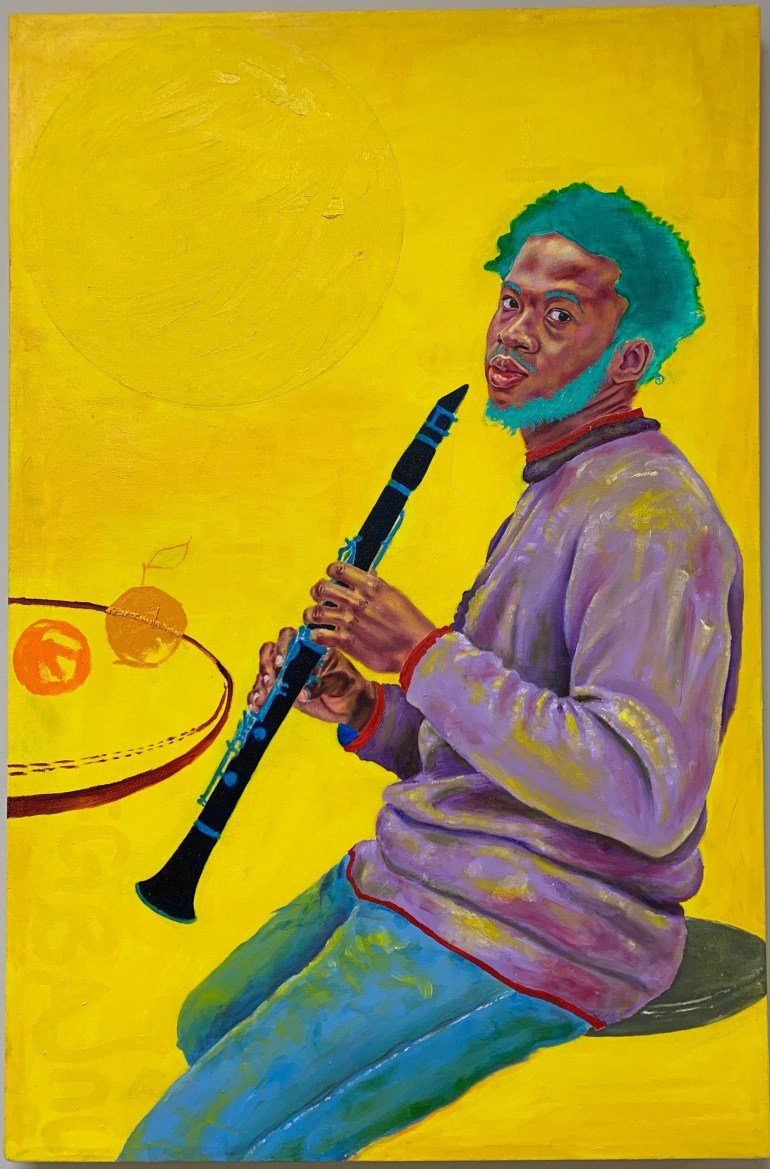

Chukwudubem Ukaigwe, “Imaobong in Ecstasy”. Oil on canvas 2018.

Tapping into spheres; from jazz music to talks of allegory, African mythology, Afrofuturism, and sound; Chukwudubem Ukaigwe is an interdisciplinary artist redefining what it means to be seen within diverse mediums. Born-and-bred in Nigeria, Ukaigwe views his work as a conversation in which he perceives sound, colours, multiple realities, and figures all in dialogue. Chukwudubem enjoys the freedom found in mobility amongst mediums.

As Ukaigwe says, “you can always find me doing work”, and this much is true. A feature-length film. Residency at the Video Pool Media Arts Centre. His work with Patterns Collective; a portable gallery that brings communities and artists near-and-far together, Chukwudubem is one of the collective’s founders. For Ukaigwe, there is always work to be done.

Subdued in manner but animated in conversation, sitting in front of a vivid self-portrait (I Don’t Want to Be Kissed), we discussed his work through our screens.

Chukwudubem Ukaigwe, “I Don’t Wanna Be Kissed”. Oil on Canvas. 2019.

IDARESIT THOMPSON: Let’s talk about your current work.

CHUKWUDUBEM UKAIGWE: My present body of work is a deep dive into the discourse of semiotics and modes of perception, with the use of specific mediums to create alternate and multiple takes that interact with each other in open dialogue.

IDARESIT: Alternate takes?

CHUKWUDUBEM: Yes. The fundamental basis of my work is borrowed from jazz music. Early jazz musicians recorded their music live, so they recorded multiple takes of the same song, in search of the perfect take. Due to the improvised characteristic of the music, no two takes would end up the same.

Musicians started to experiment with phenomena of duplicity and multiplicity. They started looking to say something else or more with subsequent takes.

IDARESIT: Multiplicity.

CHUKWUDUBEM: Like in Art Blakey & the Jazz Messenger’s soundtrack album for the French film; Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1960), one of the songs in the album titled “No Hay Problema” is a faster version of another song in the album, titled “No Problem”. The group also incorporated calypso percussion to the faster take (No Hay Problema).

Miles Davis had a recording with Gil Evans, where they had so many takes. Some of the same songs were recorded over 14 times, and every take had its peculiarity.

My work heavily depends on theory and positioning. When an art piece is placed opposite, adjacent, below, across another piece, the individual pieces conceptually stand on their own, but at the same time there’s a transcendent conversation happening between the works; it is left for the viewers to contemplate and make sense of those connections when standing in the midst of the works.

IDARESIT: Who do you hope to make these connections with?

CHUKWUDUBEM: I’ll say some of my works have a niche vocabulary [surrounding] them, but at the end of the day, I don’t think of an audience when I’m making my work. I guess my audience might be an overlapping Venn diagram of people who share the same experiences with me. I think it’s important for me to not really have an intended audience.

I’d rather have my work come across as “democratic”, and let people enter into the work through their own doors of subjectivity.

IDARESIT: Is that why you use so many different mediums? Painting, prints, film?

CHUKWUDUBEM: The job of an artist is to communicate in the most appropriate language. I feel like my approach to art-making entails being able to make a particular statement or statements in the medium or language that is most suitable. For example, particular subjects, when expressed in paintings, do not carry the same potency as when they are expressed in writing, [but] the funny thing is that it is also beautiful how these mediums overlap with each other.

IDARESIT: What does colour mean in your work? Your use of bright colours in your paintings reminds me, particularly of the Fauvist Movement.

CHUKWUDUBEM: Ah Fauvism! Fauvism was a colourful early 20th-century movement that bloomed in the intersection of post-impressionism and expressionism, [and] it’s interesting you mentioned that because I’ve always been someone who has never been afraid to explore the wildness of colour.

I think colours have sonic properties, I let them make noise (haha), sing songs, talk that talk. I should point out that contemporary African paintings of the 90s were somewhat colourful, I may have been subconsciously influenced by them.

IDARESIT: I think of the colours in the painting, Imaobong in Ecstacy, and I am, also, prompted to think of an image of the Roman god, Bacchus, at first glance. Is this an influence?

CHUKWUDUBEM: That painting, in particular, was really allegorical. That painting was a reaction to something that happened here [in Winnipeg] – Some weird, awkward racist experience.

It’s a very, very, ironic painting.

Exploring the paradox of “the tears of a clown”.

Chukwudubem Ukaigwe, “Imaobong in Ecstasy”. Oil on canvas 2018.

IDARESIT: Tell me more about your experiences in Canada – Treaty 1 Territory?

CHUKWUDUBEM: I’ve experienced a lot of things in my short time in Canada, and interestingly, my work does reflect my experiences. Most times not on purpose (haha).

I would say my time in Canada is one of the reasons I indulge in the politics of presence and absence in western art history.

IDARESIT: In what ways?

CHUKWUDUBEM: Most of the people I paint are my friends, and they are mostly Black people. When it comes to the historical lexicon of figuration, encountering painting of Black people is a refreshing experience. The other stuff has been overdone for centuries, we’re tired of that shit (laughs).

IDARESIT: Yeah, I definitely agree.

CHUKWUDUBEM: It’s interesting to participate in this renaissance of Black image-makers who are taking control of our narrative; nevertheless, I would say that there is a danger in people perceiving the work of Black artists solely with a lens that stops at identity. Some [people] are not willing to go into the context of the work. Black artists say so many things with their work, and it is unfair for writers and critics to end their analysis at mere identity and representation.

IDARESIT: I really enjoy looking at the painting, Doing it in Lagos, especially because of its reference to Nigeria. Is the title based on the album?

CHUKWUDUBEM: There’s an album?

IDARESIT: Yeah!

CHUKWUDUBEM: Actually, the nomenclature of my work is musically influenced. There’s a song by James Brown called, “Doing it to Death”, and a song by the Black Hippies called, “Doing it in the Streets“. It’s cool you picked that up.

IDARESIT: So, it’s not based on the album?

CHUKWUDUBEM: No. But now I want to check it out …

As you’ve seen, I use [music] as a [grounding idea] of how I want to approach my work in general. It [peeks] through in my new body of work, such as Doing it in Lagos or Port-Harcourtarian Ecclusiastics.

Chukwudubem Ukaigwe, “Doing it in Lagos”. Oil Paint, egg tempera and sewn in buttons on canvas. 2020.

IDARESIT: Those are a lot of Nigerian references. Can you tell me more about how Nigerian culture influences your work?

CHUKWUDUBEM: I think the Nigerian experiment [that’s what I call it], is a place of endless probabilities, due to reasons that are deep-rooted in our history. Looking at the Nigerian crystal ball from the inside and outside are two totally different episodes of the same show. Stepping out of Nigeria readjusts your gaze on the country; one is left to think, “Wow, we are really interesting people.”

I plan to go back and work on projects with this new perspective.

Nigeria is [not only a place] of endless possibilities, but it’s a place that is also rich with culture and diverse thoughts, philosophy, language, metaphysics, arithmetic, and happenings.

It’s just interesting and special.

There’s an endless space for commentary, and I think it’s more interesting than what I can talk about here [Canada].

IDARESIT: What are some of the future projects you have planned?

CHUKWUDUBEM: I really want to keep learning, and informing my practice. I hope to participate in multiple residencies over the next few years. This summer I will be an artist in residence at Salt Spring Island.

Check out more of Chukwudubem’s articles for Toned here.