Hair Care is My Self-Care

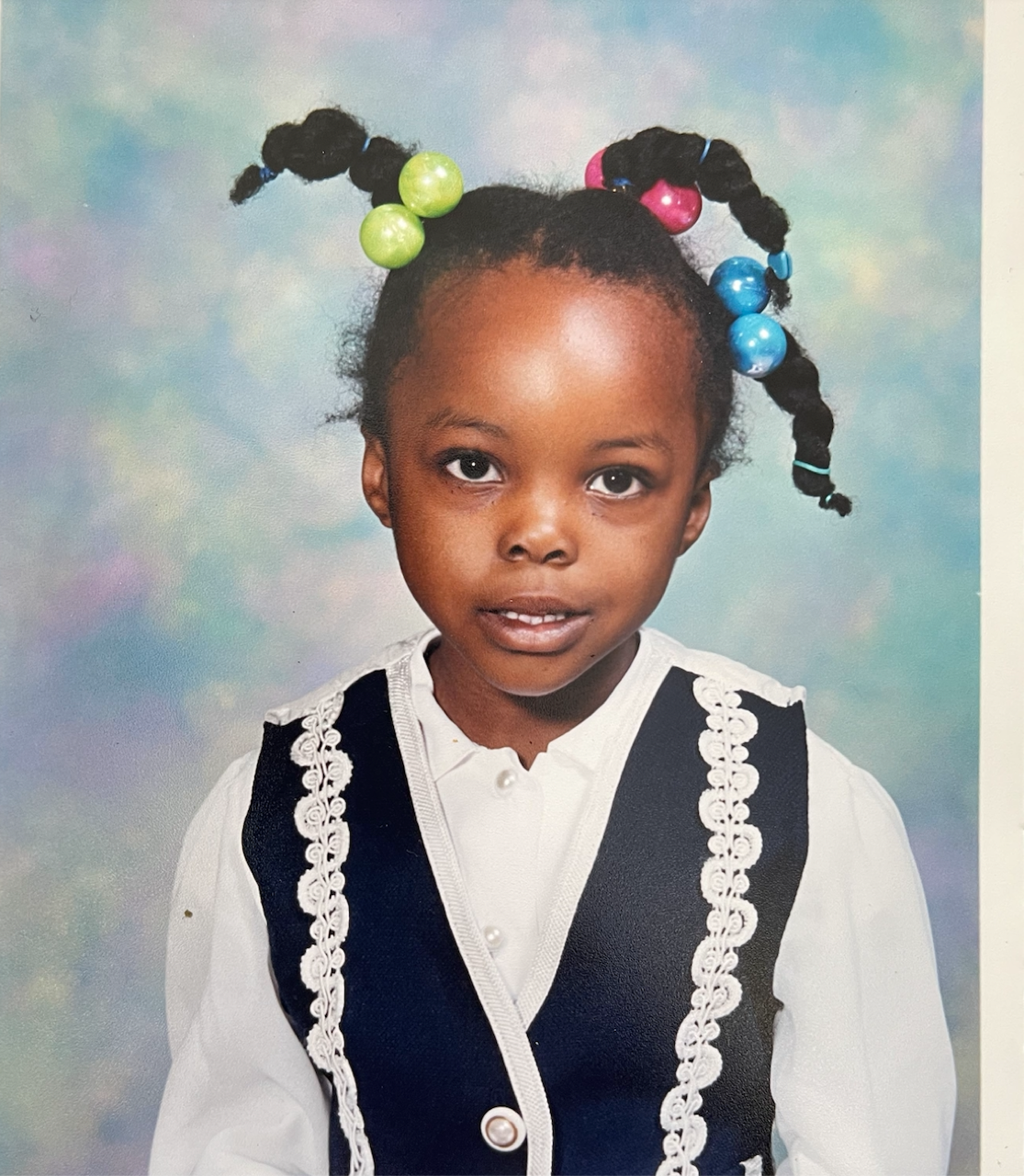

4-year-old Dorcas stands in front of the camera

Luster’s Pink Lotion was a staple during my childhood. So every time I pass by it in the Beauty Salon Warehouse aisle, I’m hit with a nostalgia that grips my feet and almost makes me want to add it to my cart. The urge to experience the white consistency, fruity essence and softness of my 4C coils is tempting, but my six-year-old hair is not my 22-year-old hair.

I no longer wear bubble hair ties, colourful elastics and huge hair clips. The hair decorations were my favourite, like a kid with their first Christmas tree. Only this time, I didn’t realize that the present was my hair. In the care of my mother and close aunts, my hair was permed in elementary, relaxed regularly and styled according to how they saw fit. I remember the trip to my aunt’s house on Saturdays every few months. Sometimes I hated it. The thought of tugging, a burning scalp and the strain of my neck made me think about a thousand excuses not to sit in that chair.

My aunt would tell me, “Beauty is pain,” and my silence was a form of agreement. It hurt, but it healed, and this code was decoded as I noticed that it wasn’t only physical pain. I grew up to find out that it was a double-edged sword. Beauty is pain. The beauty of Black hair surfaces painful experiences in society––experiences that shape our ability to care for our hair and commit to a time- and energy-consuming process.

6-year-old Dorcas at picture day in elementary.

The transition to care for my hair on my own left me vulnerable. I was learning to nurture my hair, and outsiders’ perspectives easily penetrated my low guard. I became both the teacher and student, and finding the balance was easier said than done. I taught myself how to moisturize, detangle, comb and tie my hair. It was a starting point, and I knew that I was responsible for the state of my hair. Yet, I didn’t realize I wasn’t responsible for carrying others’ opinions until I realized it took time away from my hair care.

Kinks at the roots

In Shaunasea Brown’s essay, Don’t Touch My Hair: Problematizing Representations of Black Women in Canada, Brown speaks to the historical roots of Black people’s hair in systemic discrimination. “The classification of these differences within a hierarchical sense facilitated the grounds necessary to deem the tightly coiled hair of Black/African peoples in a negative fashion,” Brown states. “The idea that Black women’s hair is trapped within a state of performance is what facilitates sentiments of self-consciousness and make Black women feel like they are constantly being watched or judged.”

8-year-old Dorcas at a school event

Black people’s hair has always been inferior to standards of beauty found in Eurocentric and Westernized cultures. However, here in Canada’s “multicultural and inclusionary space,” the lines drawn to refuse Black people’s appearance dynamics have shown that their presence and citizenship are devalued, according to Brown.

43-year-old Colleen Blake-Miller, a Toronto registered psychotherapist, speaks to the impact on our mental health. Many women of the BIPOC community live with depression, anxiety, lowered mood or exhaustion. Other words to describe some of the symptoms are struggling with our appetite, weight, lack of motivation, a sense of hopelessness, helplessness or confusion. Yet it’s just not a consideration, says Blake-Miller.

18-year old Dorcas and her curly purple wig

She stresses the upbringing within Black homes tends to shy away from conversations of mental health. “We have seen our mothers, grandmothers, aunties, and elders press and push through everything. We just expect that we should do the same. They have worked so hard for us, and we were told we have more opportunities and shouldn’t be ungrateful. We can internalize that and then think to ourselves, ‘We better not say that we are having a hard time coping,’ so we just suffer in silence,” says Blake-Miller.

This silence works its way beyond the home and into spaces that we regularly interact with. As a result, our voices are not only silenced but also our hair palette. Brown refers to it as respectability politics.

Black Canadian women engage with respectability politics that promote the invisibility of Blackness, shown through the styles they use to fit in at work. They attempt to contain their Blackness by muting the racialized markers attached to their hair as a way to make their race less visible, says Brown.

16-year old Dorcas after a few months of getting her big chop

Too many times, I’ve engaged with respectability politics. During my high school years, I explored the nuances of my hair. I regularly braided it, did weaves, put on wigs and let out my natural hair. For me, fear erupted when I had to explain myself to someone when they’d ask, “What happened to your hair?” My hostile alerts would go off, and I would hesitate to answer or ridiculously state that I took out my braids and straightened the extensions when I went from braids to a wig.

Blake-Miller talks about the stress of what to do with one’s hair. Styles that are “socially acceptable” are rather damaging to our hair. “We’ve got to process it, stretch it, or heat it up. It’s not a one-time thing. Now you got to maintain it, and I’ve got to pay all this money. The reality is, is if you’re not a black woman, you do not understand. The comments, looks, questions, it is really unhelpful and can be very damaging,” says Blake-Miller.

The weight of the word “extensions” would make me uncomfortable because I’d admit that it wasn’t mine. I’d plan my hairstyles according to what would not attract eyes or questions. This changed when I decided to do the big chop in July 2014, from grade 10 to 11. My permed hair was challenging me in ways beyond my patience and abilities, so I went natural.

Doing the big chop was exhilarating, but I started getting anxious when September was around the corner. This phase of my life gave me the self-confidence to do as I pleased with my hair and acknowledge that I didn’t owe anyone an explanation. Post-high school clarity made me realize that I didn’t need to trap my hair in a box and subject certain styles to my environment. That was 13-year-old me; 22-year old me has embraced the ups and downs of my hair.

20-year old Dorcas and her black bob

Hair salons as a safe space

One of many places that replace stares of judgment with admiration is the hair salon. Hair salons can be viewed as safe spaces for Black women given the frequency, socializing and support.

“I have many memories of sitting at my grandmother’s feet sitting in the room while my mother, my aunt spoke about things and talked. That’s how we learned a lot about our family history. I think we’re comfortable talking in those kinds of settings,” says Blake-Miller.

According to this article, Dr. Afiya, the owner of PsychoHairapy, uses hair as an entry point into mental health services. “Westernized approaches to psychotherapy are centred in a therapist’s office, which “neglects the cultural significance of informal helping networks, spirituality, and interdependence found in the Black community,” Dr. Afiya writes.

22-year old Dorcas at a photoshoot wearing her brown highlighted wig

The process, the sitting down for hours, is not uncommon for Black women. The time spent in the chair, again, is a process of hurting and healing. Coming into the shop versus leaving is not only a hair transformation but an emotional one too. Problems may not be solved within hours in that chair, but leaving environments that brought you hardships and revisiting an environment, like a salon, that calms your spirits, brings you one step closer to coping.

“The payoff is so great because then we look at ourselves, and we feel good. We feel like royalty,” says Blake-Miller. After letting my sisters tend to my hair during the majority of high school and my first year of post-secondary, I started to explore hair care environments. I went to salons and hairstylists’ homes. The feeling is therapeutic and full circle, as I would allow someone other than myself to tend to my hair and completely entrust my appearance to their talents. I felt my best when I did my hair because everything would collectively create a cohesive and liberating experience. It was also a time when I wasn’t actively doing anything but sitting down, so it forced me to reflect and assess my present situations, spaces and the relationships between the two.

Blake-Miller also brings up the need to discern. While it is a space where we can comfortably open ourselves up, we do still need to be careful about understanding the difference between an emotionally safe space versus a space where it’s okay to share. “Can I distinguish if what I share is going to be held as sacred and kept here?” Blake-Miller asks.

Living in our truths

20-year old Dorcas at the launch of her and her sister’s hair business. She decided to wear a pink bob to show how well the hair can dye.

To reclaim the narrative of what our hair represents means bringing self-care to our hair and exhibiting an unapologetic nature that doesn’t bend to the social constructions of society. Writer Hadiya Roderique talked about her hair care as a coping mechanism and discoveries of what that meant during the pandemic.

“I’ll switch up my hair when it suits or when my mood changes, leaving in one style for a week and another for a month. I find joy in seeing my hair thrive, delight in its moisture and its sheen, marvel at the mix of textures all over my scalp; a mix that used to frustrate me,” says Roderique. “I rejoice in the creativity and beauty of Blackness, as shown through the myriad of hairstyles that we can achieve. Refusing to succumb to white conceptions of ‘acceptable hair’ and showing that Black hair, in all its forms, is ‘work appropriate.’”

The essence of refusing white conceptions of what good hair is and removing words of “unprofessional,” “untamed,” “nappy,” “messy” to describe our hair is the start of living in the liberty of your Blackness. Hair was the vessel for me, and although I wish I could go back and tell my six-year-old and 13-year-old self that message, I’ll continue to love all my hair with care and attention.