A Communal Love: How Black Men Care for Each Other Through Hair

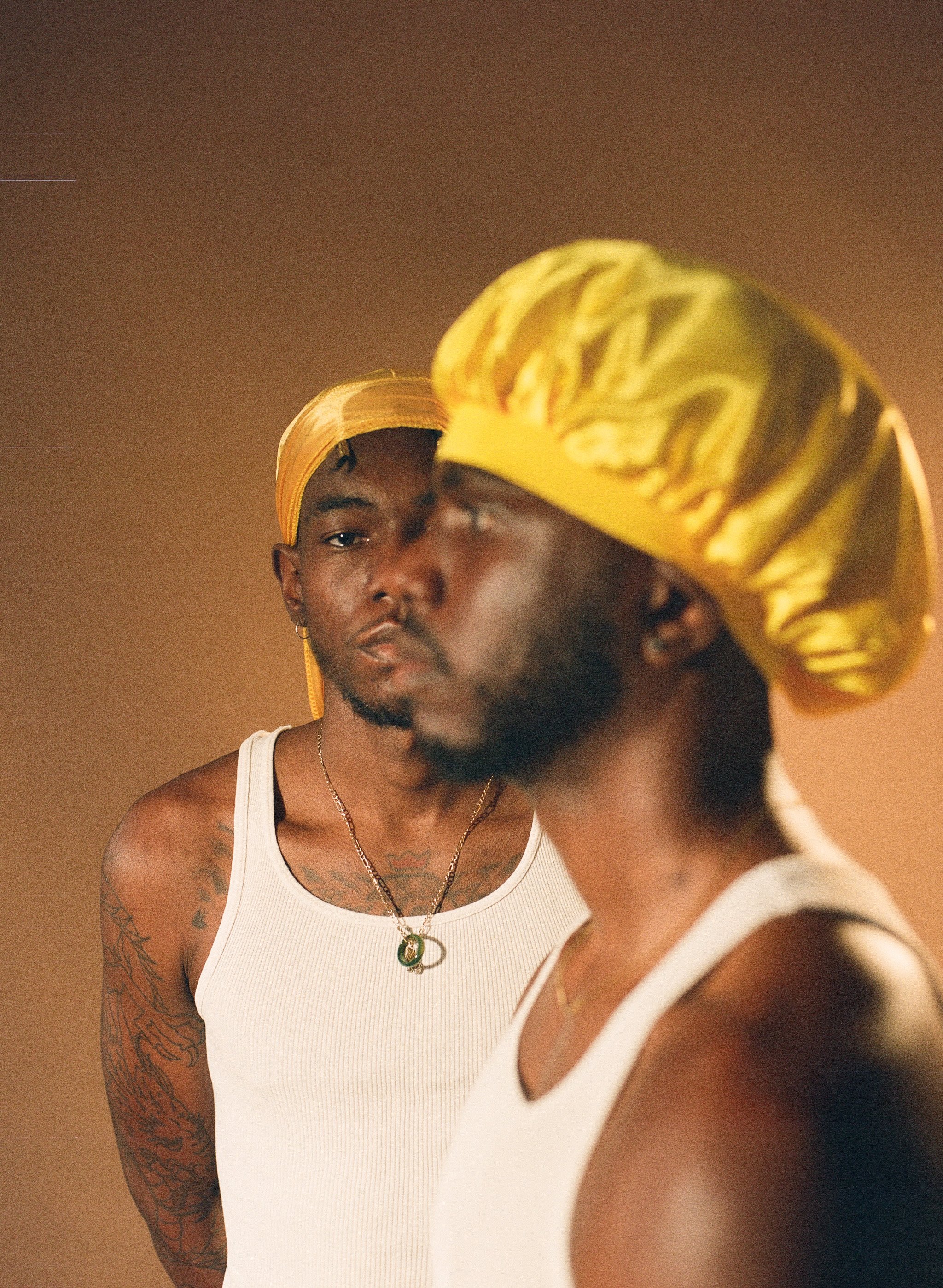

Creative Direction: Andre Harriott & Jode-Leigh Nembhard / Photography: Roya DelSol / Set Design: Roya DelSol assisted by Alicia Gayle / Styling: Jode-Leigh Nembhard / Hair: Eugenia Forskin / Models: Romel Bynoe-Shallow, Alex Stewart, Jason Lindo, Brice Baartman, Troy Harryman, Adjei Scott, Andre Harriott

As a teacher, there are moments you share with your students that challenge your worldview and what you know to be possible.

Two years ago, I experienced one of these moments. I was working with a group of grade 9 students––two of them Black boys.

We are walking side-by-side down the hallway. I am escorting the group to a quiet room in the school to work on an overdue science worksheet.

As we walk, I notice that one of the Black boys is holding a plastic bag. Every few steps, he stops, pushes his hand into the bag and runs it along the edges of the other Black boy’s head. I laugh out loud when I realize what he is doing. At this point, I have had waves for over five years; I know every styling trick in the book.

We get to the room, and the students begin working. I teach a quick lesson on ecosystems to guide them through the worksheet.

The first boy takes out a Torino brush now and starts brushing his friend’s hair. I pause for a moment––I have never seen this before––a Black male styling another Black male’s hair outside of a barber-client relationship.

I take note of how the first boy works the brush. At one point, he stops to ask me how he can accentuate the crown area. I offer some tips; he takes my advice then continues brushing. The second boy sits patiently waiting for him to finish––it’s clear to me that they have done this before.

When he is satisfied, the first boy places the brush back into his pocket and takes out a silk durag. He lays the durag on his friend’s head and proceeds to tie the loose ends at the back. He completes the knot and returns to his worksheet.

No “pause, that’s gay.” No side-eye from the other students in the class. Just Black boys caring for each other.

In many ways, this experience has shaped my thinking around Black men, intimacy and hair. I think back to the days when my dad was my barber––how he would lean my head over the bathtub to wash my hair before trimming it bald with his Andis clippers. I think back to sitting in a barber shop in Jamaica at the age of 14 and asking the barber for a double line-up––a hairstyle that had been popular among the boys in my neighbourhood. I remember the disappointment on my mother’s face when I returned home that day and she saw those two parallel lines cutting through my hair.

I think back to being a teenager who struggled to fit into a hypermasculine and hyper-heteronormative school culture. It was in high school that I learned how to distance myself from other Black men, how to preface compliments with “no-homo,” how to dap instead of hug. It was in high school that I was stopped outside the boy’s bathroom and asked if I was gay because I chilled with “too many” girls. It was in high school that my parents tried their best to police the appearance of my sexuality because to be a gay Black boy was dangerous. This looked like scolding me if I dressed in clothing that was too tight for my body and discouraging me from piercing my ears and growing out my hair. For my parents, to be masculine meant to divorce oneself from femininity while performing a constructed heterosexual identity.

As I grew older and became more aware of my own agency, I found myself wanting to jettison these limited understandings of Black masculinities. I desired more meaningful relationships with my friends who were Black men, and I wanted to seek out and create more diverse representations of Black masculinity. I found that I enjoyed seeing depictions of Black men that were different from what I was used to seeing. For me, it was both refreshing and inspiring to see Black men living fulfilling lives that were in opposition to the societal expectations imposed on them.

Now, at 27 years old and for the first time ever, I am choosing to intentionally live my life in opposition to racial and gender stereotypes.

And I have started doing this through my hair.

In November of 2020, I embarked on a new hair journey, one that has introduced me to a virtual community of Black men who are having nuanced conversations about hair. For the past ten months, I have watched Black men on YouTube and other social media platforms document their hair journeys and share hair care tips in ways that are accessible and rooted in the lived experiences of Black men (see @KingBril, @360WaveProcess, @360 Jeezy, and @TP locks). These men––who owe much of their knowledge to the labour of Black women––advise other Black men on how to properly care for their hair. In their videos, they demonstrate strategies for identifying hair porosity, evaluate the effectiveness of popular hair products, teach Black men about the importance of protective styles and maintenance, and provide detailed instructions to equip Black men with the skills needed to trim and style their hair during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As I watched these videos, I thought back to a podcast conversation I had with three of my Black male friends a few years ago. It was the pilot episode for our podcast, 3 Dreads & A Durag (this name captured our identities as Black men with two distinct hairstyles––three of us had dreadlocks and one of us had waves). In this first episode, we each shared how life experiences and family expectations impacted the decisions we made about our hair. Moreover, we discussed the challenges we faced when styling our hair along with useful strategies for proper maintenance. In another podcast episode, we discussed the politicization of the durag, underscoring the longstanding prevalence of anti-Black stereotypes that mark Black boys and men as criminals when we wear durags in public spaces (see the case of Emmel Summerville).

Currently, mainstream conversations around Black hair centre only the experiences of Black women. Despite having our own set of unique experiences with our hair, I have noticed that Black men are often erased from discussions on Black hair. For example, there has been a great deal of published children’s books that centre discussions of self-love and Black hair (see Hair Love by Matthew A. Cherry, I Love My Hair by Natasha Tarpley, Hair Like Mine by Latashia M. Perry, and Don’t Touch My Hair by Sharee Miller), however, the experiences of Black boys are rarely included in these books. Moreover, homophobia and gender stereotypes restrict the kinds of images we see of Black men’s hair. For example, Black men are often represented as barbers rather than hairdressers. We see plenty of images of Black men receiving braid-ups from Black women, but rarely do we see images of Black men receiving braid-ups from other Black men. This lack of Black-male-as-hairstylist representations reinforce heteronormative paradigms and limits intimacy between Black men.

My current hair journey has shown me that Black men are engaging in meaningful and loving conversations with each other about hair. It is through the styling of our hair that we practice agency, disrupt gender binaries and resist white supremacist definitions of respectability. It is through a communal love that we show up in support of our individual hair journeys, be it by teaching a brother the importance of wearing a bonnet at night, braiding his hair or tying down his waves.

We, too, have stories to share about our hair. We, too, have knowledge to offer. Thus, our lived experiences must be reflected in larger conversations on Black hair.